After I learned a bit about using my Polaroid camera to take pictures on paper negatives, I made up a little kit that included a Polaroid camera, tripod, a dark box with paper negatives loaded into empty film cartridges, and a changing box in which I could swap out the cartridges as I took pictures. I would then have to wait until I got home to develop the negatives to see how they worked out.

But, the Polaroid camera was originally developed in response to a simple question: “Why can’t I see it (the picture just taken) now?” Well, I wasn’t about to reinvent Polaroid film with pictures “under a minute”, but maybe I could come up with something that could produce results shortly after I took the picture.

The result? A mobile developing kit that can develop paper negatives on the field!

I just happened to have a key item to make it work: a developing drum. This version is quite small, only a few inches long and maybe 2 inches in diameter, but Polaroid-sized paper negatives fit perfectly, and it allows me to develop negatives in daylight. The idea would be to load the exposed negative into the drum, then pour developer, stop bath, then fixer into it which produces the negative. If a developing drum isn’t available, a daylight development tray can be used, or even a tank, though that would require more developer.

3 jars with the chemicals and some water would also be necessary, as well as a bucket for the water. Because I only had a homemade dark box to use as a changing bag, this kit was pretty bulky, meaning I was confined to developing negatives in my van.

My first expedition…

… was exciting — I took a picture and loaded the paper negative into the drum and poured in 30ml of Kodak Dektol and started rolling it back and forth. The first problem I found is that the chemicals didn’t pour into the drum very well. Pouring too quickly clogged the intake hole and air would stop it from entering resulting in a little spillage. Then, drops of the developer turned my fingers slippery and things turned generally messy.

But, I pressed on, pouring the stop bath and then fixer into the tank and when it was done: the magic of Polaroid was coming back. It was so exciting to see the negative right away! I took 2 more pictures, excited to see the results when the stop bath turned purple, indicating it was exhausted. I was wondering how the developer was doing since it was getting a bit dark. I had only brought around 100ml of each chemical, which I realized was too little. Then, I didn’t really have a good way to store the drying negatives, and had to end up shaking the excess water off. But my experiment was pretty successful–negatives could be developed in the field!

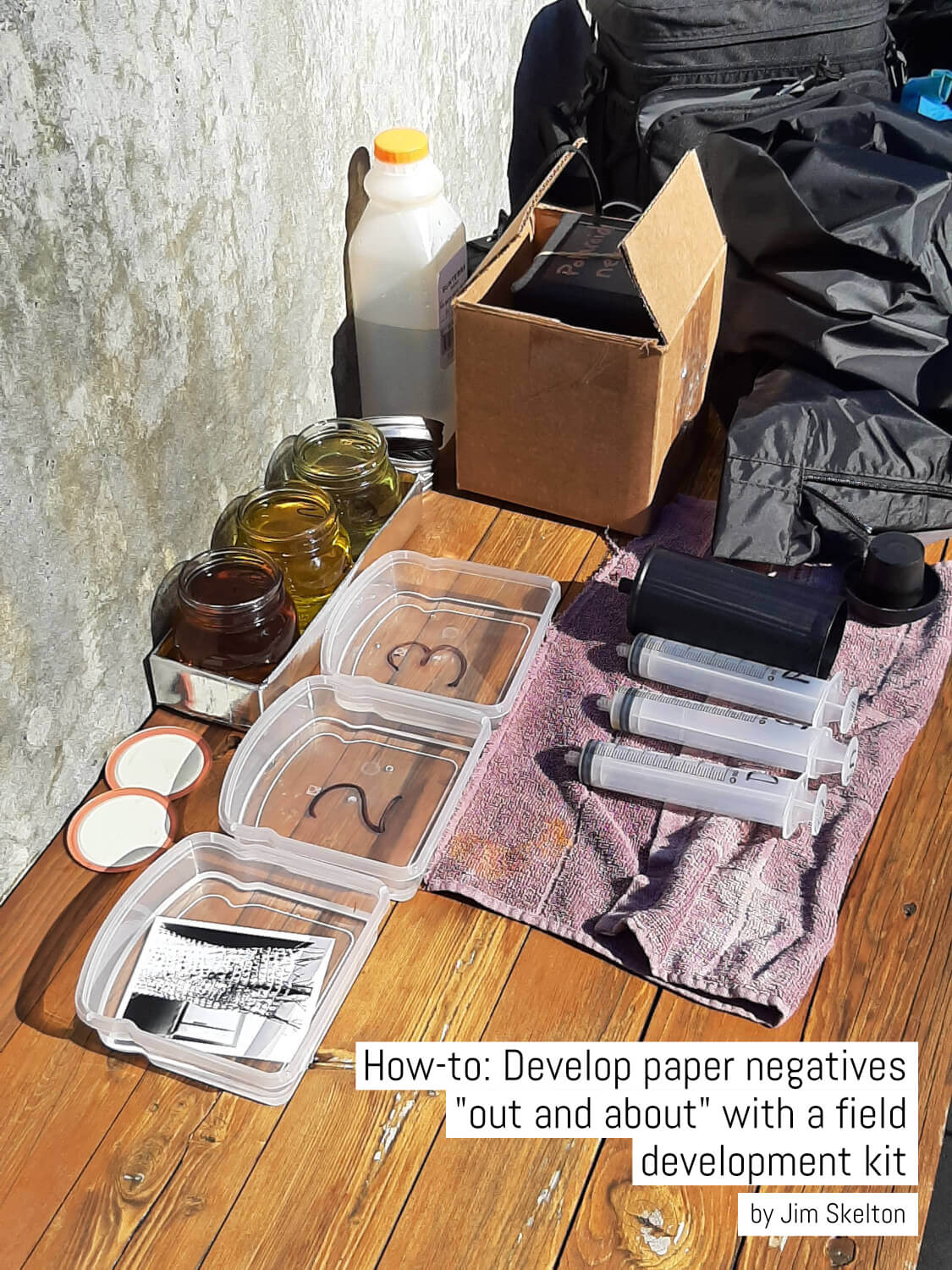

I was better prepared for my next expedition. I got 3 large syringes to measure out and administer the chemicals into the drum, some rubber gloves so I didn’t have to worry about contaminating my hands, and found 1/2 pint jars so the chemicals wouldn’t exhaust so quickly.

The second expedition…

…went much better. The syringes worked great injecting the chemicals into the drum, and the rubber gloves reduced the concern about contaminated hands. But one of the negatives seemed to be light struck. The pattern looked like it was coming from the end of the developing drum, and sure enough, it was. I found I either had to develop the negative completely in the shade, or I had to cover the ends with my fingers as I was rotating it. It’s fairly light-tight, but not under direct sunlight.

On my third expedition…

…I parked my car in a parkade and was going to take pictures around the Banff Center. I got out and was surrounded by concrete. I never left the parkade, taking and developing pictures, struck by my surroundings–that I could be in such a beautiful place but confined inside a huge concrete structure.

Developing in the field here helped me understand how paper negatives worked in a dark environment, so seeing the negatives right away was very valuable. It was also a little bit deceptive. My first picture looked like a failure, but when I did the print I was struck by the theme: being underground in a parkade looking out at the light. This process overall is helping me understand how to read a negative.

After a few expeditions, I was wondering how this could be done without being tied to my vehicle. I thought it might be fun to be able to carry a field developing kit in a backpack and set it up anywhere. The biggest issue is rinsing. It takes a lot of water and water weighs a lot. I also didn’t want to contaminate my surroundings by dripping chemicals on the ground or having to toss rinse water out, and all of this had to fit into a backpack.

I finally got a camera changing bag, which greatly reduced the size of the kit and came up with a rinsing scheme:

- I would carry 1 liter of water, an empty liter container, and 3 rinsing trays.

- The trays would each contain around 150ml of water and the negatives would be rinsed in each tray for around a minute.

- When a negative was finished its rinsing sequence, the first tray of water was tossed into the empty waste container and the tray was placed as the last rinse and filled with 150ml of fresh water.

In theory, I would be able to fully rinse around 6 negatives using only 1 liter of water.

Another challenge was coming up with 3 jars that didn’t leak. This wasn’t as easy as it sounds. Canning jars seem to be the best, and they came in a tray that would keep them together in the bottom of the backpack. The drum, trays, squeegee, and drying rack were put in a box on top. The tripod and water were squeezed into the sides, and a couple of rags, a mat, and the changing bag were stuffed into the cracks. The negative dark box fit on top. It was exciting to see it all fit into a backpack!

My first truly portable experience developing negatives on the field was a lot of fun. I walked down a path to a bench and set up there. As I was taking pictures and developing them, I noticed something change in the way I was experiencing photography. Though I found shooting with film using manual exposure had slowed down the process of photography and made me think more about what I was doing, adding the development process seemed to add another dimension to my experience.

First, seeing the negative right away was not only delightful, but it also gave me immediate feedback as to how the photo turned out, and allowed me to retake the photo with different parameters for different effects. And, the process of developing the negative right away slowed down the photographic process even more. Time flew by as I immersed myself in photography, and packing up and leaving with developed negatives was satisfying.

Yes, this process only produces negatives. So I’ve been mulling a predictable process to produce contact prints on the field using ambient light. I’m not sure it’s worth the trouble since contact printing in a darkroom is so much faster, and things like test strips would be quite difficult on the field. Of course, I could try direct positive FB paper, but it would have to be rinsed much more thoroughly than resin-coated paper.

But another idea came up: shooting and developing paper negative reversals on the field. This would produce a positive print right away, emulating the Polaroid process. Then, my Polaroid could be a Polaroid again!

There are limitations to this process. Temperature is the main one — it has to be a nice day out so the chemicals don’t get too cold, and it does require some space to set up. And, it requires time, which I have to find more of somehow. But, of all my photo expeditions I remember, the fondest memories so far are the ones where I developed the negatives on the field. I look forward to developing both paper 4×5 negatives on the field in the future, as well as possibly developing film and lith negatives as well.

Oh, and you may have a nagging question in the back of your head. How did the 3 tray rinsing process with minimal water work out? Well, my first field developing session was over a year ago, and the negatives are still in good shape!

~ Jim

Share your knowledge, story or project

The transfer of knowledge across the film photography community is the heart of EMULSIVE. You can add your support by contributing your thoughts, work, experiences and ideas to inspire the hundreds of thousands of people who read these pages each month. Check out the submission guide here.

If you like what you’re reading you can also help this passion project by heading over to the EMULSIVE Patreon page and contributing as little as a dollar a month. There’s also print and apparel over at Society 6, currently showcasing over two dozen t-shirt designs and over a dozen unique photographs available for purchase.

One response to “How-to: Develop paper negatives “out and about” with a field development kit – by Jim Skelton”

Much too complex and complicated for me – but a noble experiment nonetheless!

Amazed at such good images you got with such primitive techniques… no offense meant by this, ha! My admiration for what you have done is truly genuine.

Best, DANN