Jazz has a special place in my heart. It’s a musical language that somehow, I can understand by simply freeing my mind and letting the music run through my soul. Last summer, I was preparing my applications for graduate programs in photojournalism. I figured my portfolio was lacking in the documentary department, so I set out on a mission to push myself to tell any story.

It so happened that I was shooting event photography for a Jazz and Hip-Hop show called Backbeat LA at the time. I was constantly exposed to a group of talented and innovative young artists who were expanding jazz further into the depth of the universe. The artist who stood out to me was Mekala Session, a drummer whose percussive talent is unparalleled, and whose musical lineage extends to one of Los Angele’s legendary jazz groups, The Pan Afrikan People’s Arkestra.

Since this article will be focused on the technical aspects of the shooting process, I’ll leave the link to the full story on my website, here.

The decision to shoot the story on film was a mixture of artistic vision, experimentation, and wanting to make things more complicated for myself. Jazz is jazz and film is cool and the texture and analog aesthetic of film photography seemed to suit the story. I never know what I’m going to get back from the lab when I get my film developed, just like I never know what I’ll get at a jazz show, and that was enough put my 5D down.

The camera of choice was the Nikon FM2n. I picked this body up from a Japanese store on eBay. We all know the ones. This camera, as far as I’m concerned, is one of the best developed. It’s made for a photojournalist. The body is built like a tank, with a robust metal chassis and solid controls that have satisfying haptic feedback. It shoots mechanically up to 1/4000th of a second, the “N” version with a 1/250th flash sync, and is completely manual. This means no batteries necessary, only for the light meter. If the world came to an end and I had to pick one camera to use in the apocalyptic future, this would be it.

The lenses I have were given to me by my dad. The 50mm f/1.8, 35–70mm f/4, and the 105mm f/2.8. Most of the photography in this story was shot on the 50. I love the focal length, and whether its film or digital, when I walk around it’s the lens I probably have on my camera.

Film. It had to be Kodak Tri-X 400. There’s a reason it’s a choice for most documentary photographers. You can use it, abuse it, push it, pull it, and it gets the job done. The grain is pleasing, the dynamic range expansive and it’s very forgiving in difficult lighting situations. I also think that it’s the film of jazz.

PORTRAIT – MEKALA SITTING ON COUCH

Mekala Session, known as “Mickey” to his friends, sits on his couch in his garage studio. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

This was the portrait of Mekala that I chose to be the cover of the story. He was sitting on the couch of his garage studio and there was incredibly harsh sunlight coming in from his right.

I exposed for the highlights and got the drama I wanted for an opening image. The way the left side of his face falls into shadow but retains the catchlight in his eye sold it. I think this is a good example of how even pushing the dynamic range of film beyond its limits yields some cool results.

SILHOUETTE OF MUSICIANS IN GARAGE

Jamael Dean (left) and Aaron Shaw (right) of the Afronauts discuss logistics between songs for their upcoming performance. Many groups come to Mickey’s garage for practice sessions. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

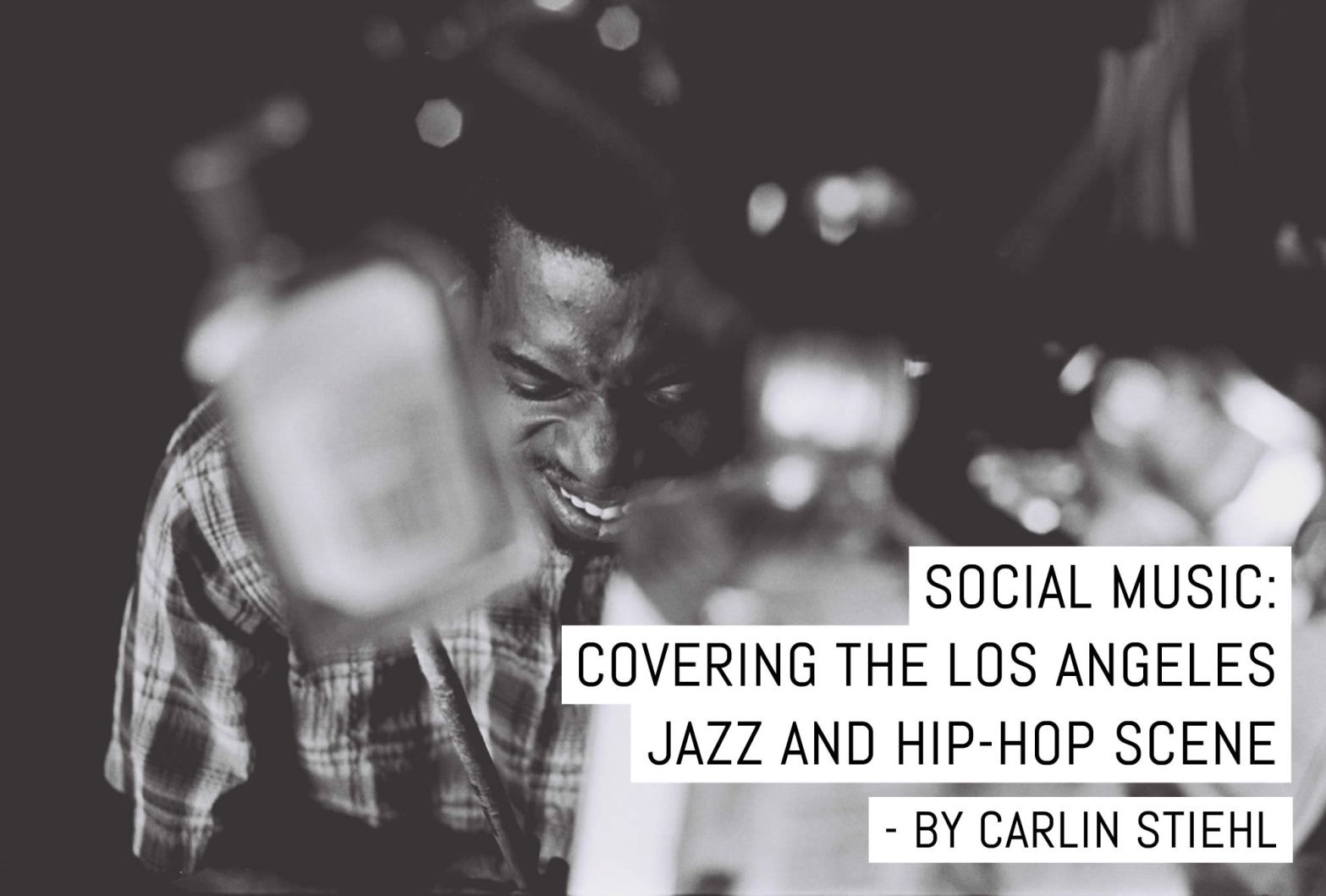

FRAMED SHOT THROUGH GLASS BOTTLES OF MEKALA DRUMMING

Mickey plays various beats during a solo practice session. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

One of the biggest challenges of this story was the underground nature of the performance venues. There was no light, which is a death sentence for a photographer. For these scenarios, I had two options. Push the film up to 3200+ or use a flash. The problem with pushing film that high, and what people don’t tell you, is that you still need light to react to the film. Pushing is not a solution for low-quality light and will leave photos with an unpleasing muddy grain.

The push comes in handy in decent lighting situations when I want to get the shutter speed higher, stop down on my lens, or to achieve an aesthetic result. So, flash it was.

FUNNY FAE TONGUE OUT

Mickey hangs outside of Delicious Pizza in Los Angeles before a rap performance. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

MEKALA DRUMMING WITH POWER JAZZ FACE

Mickey’s solos are often met with faces in awe from an inability to comprehend the sheer power and momentum of the rhythm he creates. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

Which flash, you ask? The Nikon SB-22s fully manual automatic manual flash. And by that, I mean plug in your camera settings on the back, stand at the right distance, let the automatic light meter do its work, and hope for the best. To be perfectly honest, this was my first time shooting flash on film, and what better way to learn than on the job in critical moments I don’t want to mess up.

Adapt or die.

GUY COOKING JAMBALAYA

The return of the Ark is a community event, bringing Leimert Park together for a night of festivities. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

GUY SINGING WITH HIS ARMS OUT

Dwight Trible, the current executive director of e World Stage, steps in to sing “Little Africa.” Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

MEKALA MC ON MIC

Mickey introduces the Arkestra. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

GUY SMOKING CIG

Jazz and hip-hop events do not just occupy the inside of a venue, but rather the whole block. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

The flash turned out to be incredibly useful. It never failed me. It gave me amazing results, allowing me to capture defining moments in performances and images that without it could not be possible. My only concern was that on-camera flash constantly looks like on-camera flash. Oh well.

I think people overthink film as this unattainable fearful medium, that if you don’t nail exposures or have years of experience, you’ll be destined for failure. It’s actually quite easy. Just pick up a camera and shoot. Negative film is incredibly forgiving (NOT SLIDE FILM), loves to be overexposed, and mistakes can yield amazing results. Whether the images created are good, well, welcome to the competitive world of photography.

PHOTO OF BASS

Eli Shaw of Black Nile plucks a baseline that the group builds off of. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

TROMBONE MAN

Zekkereya El-Megharbel, a member of the revived Arkestra, solos on his trombone. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

As much as this journey was about telling a story about jazz, it was a learning opportunity on how to shoot 35mm film. Each time I received my negatives and scans back, I learned more about the nature of how Tri-X works – How light reacts to it, what scenarios it performs in best, how to become one with the film.

TV ON THE COUCH

A broken TV rests on a discarded sofa in Mickey’s backyard at his Inglewood home. Shot on Kodak Tri-X 400.

Photography is about storytelling, and each story deserves its own special touch, whether it’s a format or approach. Although I mostly discussed the technical aspects of how I captured these images, I encourage people to view the final work I created and learn more about Mekala, The Arkestra, and the world of jazz. In the meantime, I’ll be studying at Ohio University to become a stronger storyteller, and create more projects like this.

~ Carlin

Share your knowledge, story or project

The transfer of knowledge across the film photography community is the heart of EMULSIVE. You can add your support by contributing your thoughts, work, experiences and ideas to inspire the hundreds of thousands of people who read these pages each month. Check out the submission guide here.

If you like what you’re reading you can also help this passion project by heading over to the EMULSIVE Patreon page and contributing as little as a dollar a month. There’s also print and apparel over at Society 6, currently showcasing over two dozen t-shirt designs and over a dozen unique photographs available for purchase.

2 responses to “Social Music: Covering the Los Angeles jazz and hip-hop scene”