When Photo Clubs announce a contest named “Fallen Leaves”, most participants will think of autumn. Images of red maple leaves floating in a still pond come to mind, as well as stands of birches, their yellow leaves and white trunks brightening the reflection in a dark mountain lake, and the list goes on.

This is scenery of such undeniable beauty, offering so much to the photographer, that I can’t even make cynical remarks. These views have fuelled the motivational poster industry for at least three generations of photographers. Our gardener would have hated it; it implies more work.

To me, autumn foliage is something exotic I haven’t seen in over 50 years. When I think of fallen leaves, I envision either decaying leaf litter or I’m reminded of skulls.

Here in the tropics, many plants have fleshy foliage that either loses water, dries and shrivels away, or falls to the ground and is rapidly decomposed and integrated into the soil. The more interesting ones, to me, are the leaves that slowly lose their fleshy parts, revealing their underlying structure: their skeleton, their skull.

Skulls are the essence of an animal. You look at a skull’s shape, and you can learn a lot about the animal’s behavior, its diet, how it moved. You can notice if it is diurnal or nocturnal, if it hunts by sight or smell, and how it kills its prey.

Much like animal skulls, there are leaves of many species of plants that can also tell stories. But they must be fallen leaves, a very different animal from green leaves.

The process that causes leaves to fall is abscission, an aging process that alters the leaves´ composition, structure, and shape. As the leaf ages and changes, many of its components change, increase or disappear. Shamans, chefs, and ethnobotanists know that there are many recipes that call specifically for fallen leaves of different plants, because they know the chemistry of the fallen version is quite different from the leaves still on the tree.

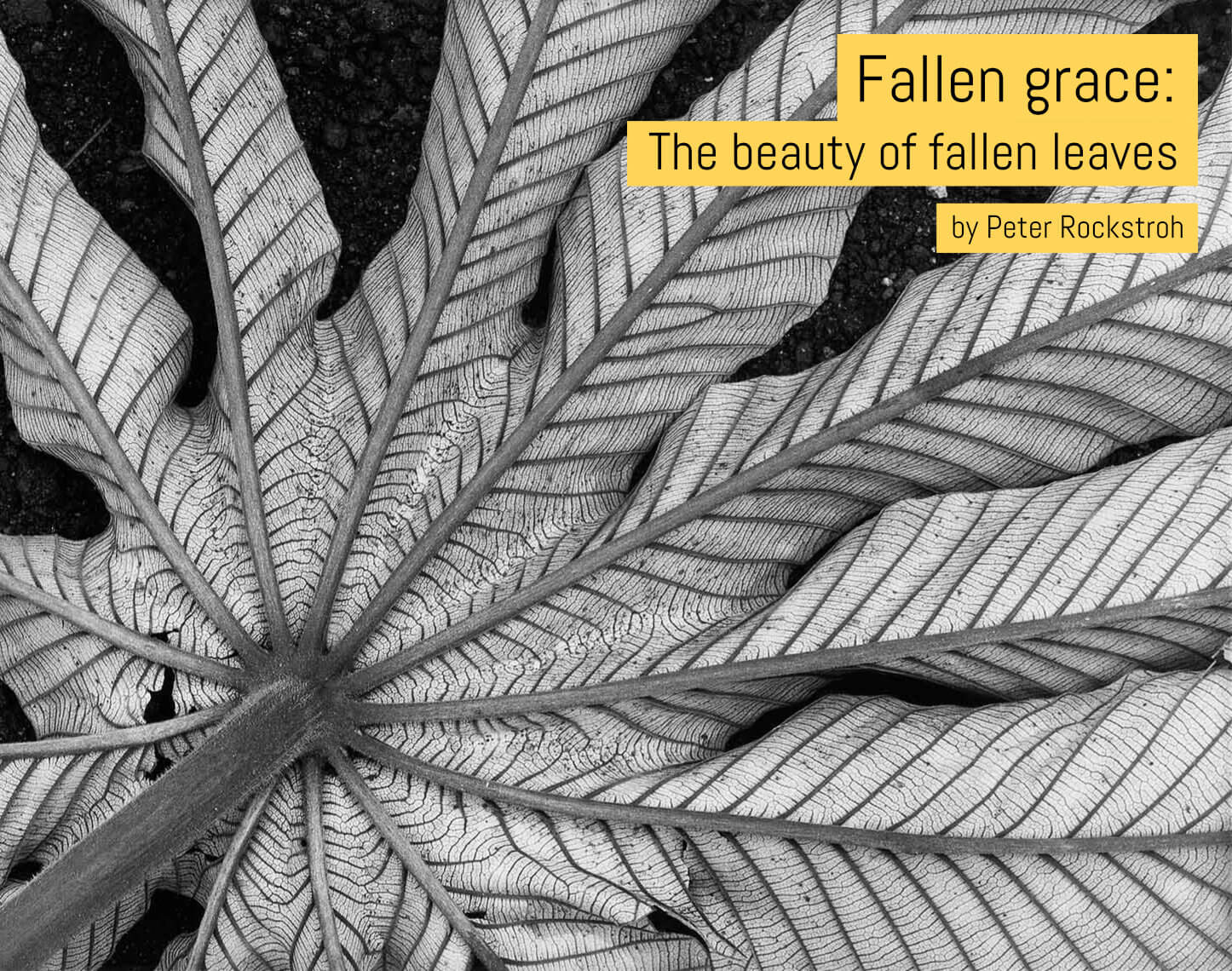

I photographed this palm leaf in Tikal National Park, Guatemala, on an overcast morning with an 8×10 camera. I set the camera up and while focusing thought about tilting the ground glass to get everything in focus. Fortunately I didn’t, because that would have deformed the leaf, making it look strangely larger and not uniformly flat.

To get everything in focus, rather than focusing with camera movements, I stopped down the 240mm lens to f/90 and exposed the negative for 4 sec.@f/90

My main interest lay in the composition between the leaf and the roots of the tree behind it. I was so focused on getting that relationship right, that I forgot to pay attention to the rest of the image.

My first contact prints looked very promising, but it wasn’t until I printed my first enlargement that I realized how rich this image was. After many years I still get lost in the detail of this photo.

I used to think that grandiose landscapes deserve to be printed big and intimate details of landscape should be of a size that requires an intimate, up-close viewing experience.

In photography, there are only a few rules, and one that I respect is that print size depends on the image and not the subject matter, EXCEPT for baby photos. Baby photos should NEVER be larger than 11”x14”; and NEVER EVER larger than the baby.

Back to leaves.

Leaves from the Indian almond (Terminalia catappa) possess a broad range of antibiotics, and are frequently used to quarantine tropical fish. But these properties are only held by fallen leaves. Attempts to pick green leaves and dry them artificially for appearance (looks) failed to show the leaf´s antibiotic powers.

Cecropias are fast-growing trees that rapidly colonize new light gaps in the American tropics. They form large stands along river edges, dispersed by running water, or along the edges of clearings, dispersed by birds, after the seeds have passed through their digestive tract.

They also contain a toxic latex which, no doubt, makes them less appetizing to the microbiological communities in charge of reintegrating them into the soil. Their structure and microstructure remain clearly visible a long time after having fallen to the ground.

When I found this leaf (below), it showed an amazingly crisp pattern of black and white micro ornamentation, but it also showed some beautifully textured areas that deserved a major role in the composition of this image. I walked around the leaf four or five times, until I found the composition I was looking for.

The image was taken with a Pentax 67 on ILFORD HP5 PLUS and has been printed on a very broad range of papers, in the days when there was a very broad range of papers.

This image was scanned from a copy printed on Oriental Seagull.

I took an average reading of the scene and developed 40% longer than usual. I blew out the highlights of all the landscape images I had taken on the same roll, but none of them got close to this image.

The longevity of dead leaves (Schröder’s First Law of Botany) also depends on the amount of lignine they contain (the hard, shiny resin, that gives its gloss to bamboo stems, many seeds, and palm leaves). It is a structural resin that gives very high mechanical resistance to plant tissues.

The leaves that I like photographing are those with veins and stems high in lignine, as their structure retains a beautiful gloss that contrasts with the rest of the leaf. (see below).

I found this scene walking on a riverbed of a creek that was slowly getting drier by the day. I sat down with the sun shining intermittently over my shoulder and searched for a spot that would give me a side-lit image to enhance the texture. What caught my eye was that every part of the image was wet, but there were many contrasting textures. The leaf had probably been carried there by the small stream and although there was no running water anymore, the sand around it was still wet, the tiny marble particles glistening in the dappled sunlight.

As I laid down I put a close-up lens on my camera and lowered the tripod to less than 10 inches.

I crouched as good as I could to compose the image, took the meter reading and added a few frames. I normally do that when I think I found some extraordinary image and remember my chances of getting a kink in the film during development — or two negatives stick together. When those memories emerge, I make sure I have another copy!

Remember the first photo? Here it is again. The large palm frond is lying on top of a carpet of leaf litter from many different species. The fan-shaped frond is covered with a myriad of algae, lichen, fungi and epiphytes. Palms play a major ecological role in the humid forests they grow in. While eucalyptus trees shed even their bark, to avoid any epiphyte growth on top of their structure, palms are gracious hosts to many epiphytes. From the thick stands of ferns and aroids frequently growing in the axils of the old petioles, to the myriad of mosses, lichens, and fungi growing on their leaves.

Technically it is also a beautiful subject, particularly during overcast days. I have learned to enjoy this type of image when I started using extended development. What makes the subject beautiful when you can produce images that have the right contrast to enhance textures and give the image a three-dimensional pop.

My first tests using longer development times were done with landscapes, where I successfully managed to blow out all details in clouds and sky. On top of that, since extended development enhances grain, large, textureless surfaces such as blue sky, look mottled and uneven. Up close they show the little black dots which are the space between the actual silver particles.

I try to stay away from large, textureless areas and look for compositions with wall-to-wall content.

Fallen leaves are not necessarily a symbol of death; they can also be a symbol of growth. Many trees take a long time until they produce mature, fully developed leaves.

Madhuca longifolia (Mahwa) and Santalum albumindian (Sandalwood) from India, are both wild harvested for their medicinal leves. The trees are ripe for harvest when the leaves can be sun-dried and beaten with a brush until their skeleton is visible.

This image was taken with a Pentax 645 and developed with normal development time and temperatures. Although it shows the leaf skeleton in all its detail, it doesn´t have the sense of volume of the other images. It lacks the local contrast from the extended development, although it gives a much more faithful rendition of the soft filtered light coming through the canopy.

The overall contrast in these scenes is rarely more than three stops, so I can expose for the average value or one stop more, when they have very valuable information in the shadows. I didn’t use my normal developer, at my standard developing temperature and agitation and added 40% development time. That is about the equivalent of N +1 (Normal + 1 Stop) development in the Zone System.

Of course, that approach works for many subjects under those light conditions. Extraordinary leaves are just a single subject that captures my attention every time I have the opportunity to find one of these amazing structures.

Thanks for reading,

~ Peter

Share your knowledge, story or project

The transfer of knowledge across the film photography community is the heart of EMULSIVE. You can add your support by contributing your thoughts, work, experiences and ideas to inspire the hundreds of thousands of people who read these pages each month. Check out the submission guide here.

If you like what you’re reading you can also help this passion project by heading over to the EMULSIVE Patreon page and contributing as little as a dollar a month. There’s also print and apparel over at Society 6, currently showcasing over two dozen t-shirt designs and over a dozen unique photographs available for purchase.

3 responses to “Fallen grace: The beauty of fallen leaves”

These are beautiful images, Peter. Your technique of extended development to augment the sensation of depth that large format delivers is interesting. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you John. I think the improvement is even more visible in medium format, although I’ve used it mainly with Pyro with roll film, while I have used standard chemistry (D-76, HC-110) for extended development with sheet film

Thank you John. Thanks for your comment. I just realized that most of my LF images of this kind almost never show sky areas, so I rarely have a problem with overall contrast being higher than local contrast. When your image only has a 3-Stop range, exposure and development are more forgiving.